At first, size was clearly more important than brains: When mammals seized power after the dinosaurs went extinct, they initially only enlarged their bodies and retained modest brains, a study shows. The researchers explain that only when it became widespread after about ten million years did many species begin to invest in enhancing their cognitive abilities in order to gain competitive advantages.

They have particularly highly developed brains, and mammals have also produced the smartest organisms in the course of evolution: humans. The cognitive performance of this group of animals is related to the relationship between brain size and body dimensions. The following rule applies here: the more brains there are compared to the mass, the more intelligence an organism can produce. Although the brain of elephants is much larger than that of humans, we are still cognitively superior to them. However, one could essentially ask why not all animals simply developed bigger and bigger brains. The reason for this frequency is the massive energy consumption of nervous tissue. So the increase should be worthwhile, which is not always the case. After all, animals have greater chances of survival and reproduction only if the benefits of more intelligence outweigh the costs of investment.

Targeting dinosaur successors

Apparently, this was often the case in mammals – there is a similar trend in their evolutionary history. But there are still unanswered questions about the pathway of so-called cerebral fermentation. In particular, there was a gap at a crucial stage in mammalian “occupations”: there is little evidence of brain development immediately after the mass extinction event 66 million years ago — when surviving mammal species began filling the abandoned ecological niches formerly occupied by dinosaurs.

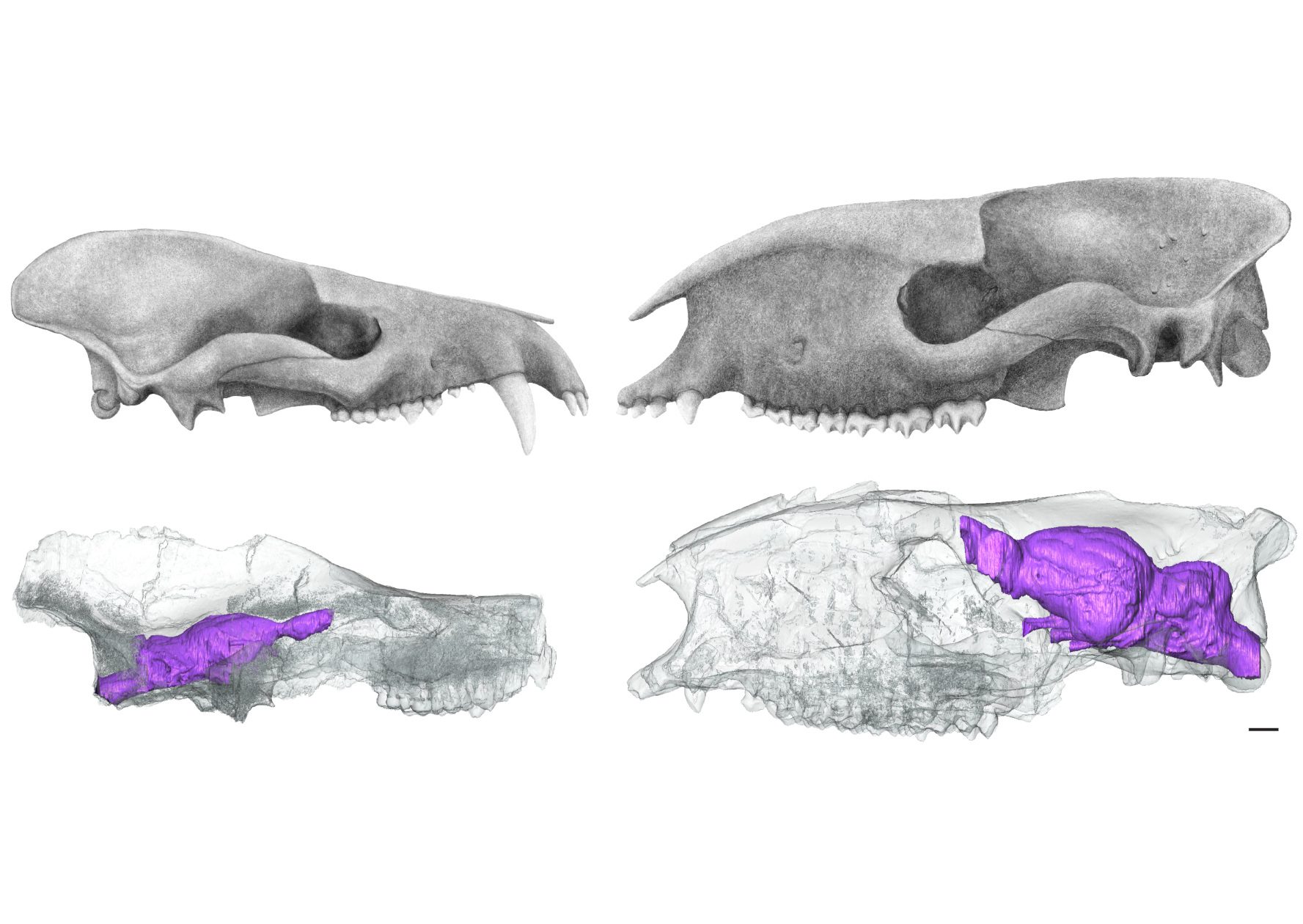

In order to gain insight into the evolution of this era, scientists led by Steve Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh examined fossils from a total of 124 extinct species, which date from the early period of mammalian evolution to the Mesolithic. Their study was particularly rich in data on the crucial period immediately following the end of the Cretaceous period. As part of the investigations, the scientists recorded the animals’ body sizes and the characteristics of their brains. In addition to the general size, they also used CT scans to examine structures in the skulls that could provide clues to the developmental status of certain areas of the brain.

Big Pioneers With Small Minds

The results showed that the size of mammalian brains compared to their body weight initially decreased in the first 10 million years after the asteroid impact 66 million years ago. The scientists reported that the detailed results of the scans also indicated that these animals tended to rely heavily on their sense of smell, and that their eyesight and other senses were relatively underdeveloped. Only later did the trend reverse. Obviously, being tall was more important than being smart at first in order to succeed in the post-extinction period. In other words, “the mammals that replaced the dinosaurs were pretty stupid at first,” says senior author Brusatte.

According to the scientists, the results demonstrate once again that large brains and powerful sensory systems are not necessarily beneficial for evolutionary success. Lead author Ornella Bertrand of the University of Edinburgh explains: “Maintaining large brains is costly, and if resources are not essential, potentially detrimental to early mammal survival in the chaos and turmoil that followed an asteroid impact.”

But this changed later: as documented by the results of scientists’ research, after the stage of a rather weak-headed mammal, which lasted about ten million years, some of the more recent representatives in particular developed larger and more complex brains. Sensory performance and motor skills. Scientists see the reason in the fact that there is increasing competition for resources. It appears that investing in more brains could increasingly pay off and outpace the costly nerve tissue costs.

Source: University of Edinburgh, professional article: Science, doi: 10.1126 / science.abl5584

“Alcohol buff. Troublemaker. Introvert. Student. Social media lover. Web ninja. Bacon fan. Reader.”

More Stories

Simple recipe: sweet cream cheese slices from the tray

This is how our brain chooses what information it will remember in the long term

Up to 100 pilot whales stranded in Western Australia – Science