Even “three???” Dedicate a ring on fire

Mervyn’s life story, like that of thousands of other people from Centralia, will forever be linked to the coal fire. The most popular theory about its origin: On May 27, 1962, several members of the volunteer fire brigade were supposed to “clean up” a garbage dump in a former open-pit mine. From there he is said to have jumped into other pits and slowly made his way through the maze below the city.

Despite many attempts, the fire could not be extinguished. Instead, he made deep incisions in the streets. Plumes of poisonous smoke rose from the ground. In some places the ground receded. Centralia Center, where little evidence of fire is seen or smelled today, has become a national disaster.

The place was also famous in Germany when the radio series “Die Drei???” was shown. He dedicated the episode “The Burning City” to him. In the 1980s, Centralia was finally evacuated, abandoned homes became state property and were demolished. But few residents refused. One of them was Mervyn’s father. “My dad was a fierce fighter,” says the 72-year-old. “You know he wants to stay. He said the fire didn’t matter.”

After a few years away from Centralia, Harold Mervine came back here in 2014, growing up playing baseball and wandering in the woods with his friends. Today he lives alone in the house that his grandfather built over 100 years ago. He says he would not have been able to see it if it had been demolished. His father used a running lawn mower to tame the lawn around the property for years. Three, sometimes four days a week. At some point as he got older, “things were bloated.” When he died, he left his son alone.

A visit from the ghost hunters

Mervyn says he has nothing against the fact that spectators regularly come to Centralia. But people were only driving across the deserted road network, wherever they could go by car. “Then they leave. They have no idea what they saw. They don’t talk to anyone. They just wander around and walk around.”

A few weeks ago he heard a noise in the middle of the night. They came from the other side of the main road. Mervyn went to check on things. He counted eight or ten cars. A man asked him exactly where the old train station was. Of course he knew Mervyn, but he asked strangers why they were looking for him in the dark. They were ghost hunters.

Today, Father Francis DeRosa stands on the sidewalk across State Road between two overgrown ledges just three minutes from Harold Mervyn’s home. DeRosa wears a white collar under the priest’s black robe. He’s a trans from Virginia and a little scared of Centralia and its history.

“This is a ghost town,” that is the first thing he says, even before he introduces himself. “You get goosebumps here.” All homes are gone forever, and the area is damned. “I’d be careful. I mean, I don’t know. But don’t you think you should be careful in a place like this?”

A sign in the cemetery warns: “You are being watched.”

Centralia is a three-hour drive west of New York, and underground visitors fear little for life and extremities. But the possibility of falling into paranoia at nightfall is real. One of the three earlier cemeteries in the south shows how many people lived – and died – here. Dozens of rows of tombstones bear the names of Irish, Ukrainian and Lithuanian residents. Nobody is here, but a sign at the entrance to the tomb of Saint Ignatius warns: “You are an observer.”

On the way back to the rental car, it turns out that even those who dare otherwise can become paranoid. The door closes, and it’s quiet, but looking in the rearview mirror makes you amazed. He must have been in disguise. Maybe an error when going down. However, the view is like Hollywood in the back seat. empty. But below, on the floor, is an unfamiliar plastic bottle. The people at the rental car forgot about it when cleaning. or?

Two minutes’ drive away, Thomas McGinley stands in front of his car, greeting the phrase “How are you?” And a smile nip any thoughts of coal fire ghosts in the bud. He’s the son of Centralia, but he’s one of those left. McGinley has only fond memories of his childhood.

“It was friendship — not just from friends but also from their families,” he says. Badges of life amidst the proud American industrial engine where everyone worked hard and held the community together. “It was a special place. It really was,” says McGinley, who serves as a prison warden in the area.

ghost town souvenirs

Meanwhile, Harold Mervyn is walking down Old Central Street in Centralia. He’s skinny and frail-looking, his buckled jeans fluttering around his legs. But his steps were sure, and after a minute he turned right toward a staircase surrounded by low branches and bushes. Indicates the adjacent wall that is missing stones. He simply says, “People started stealing everything they could.” Centralia souvenirs.

He climbs up a broken step and stands seconds later on the edge of the court, which he once knew every corner of. He played baseball with his boys here almost every day, with his best friend Billy mostly at his side. Mervyn points to where the first base was. favorite position. And as a hit, he hit the ball as high as possible into the Pennsylvania sky.

Decades later, weeds that reach the waist are buried past. “There are a lot of things that aren’t really visible,” Mervyn admits. On the other hand, Thomas McGinley says of the greenery that blanketed Centralia, “As long as these plants grow, they can’t hide the memories.”

And Harold Mervyn’s home in Centralia will one day be razed to the ground, too, even if he dies. He says it doesn’t make any difference anyway. But for now he’s dropping the steps and back on Troutman Street. He still wants to mow the lawn around his property.

“Award-winning music trailblazer. Gamer. Lifelong alcohol enthusiast. Thinker. Passionate analyst.”

More Stories

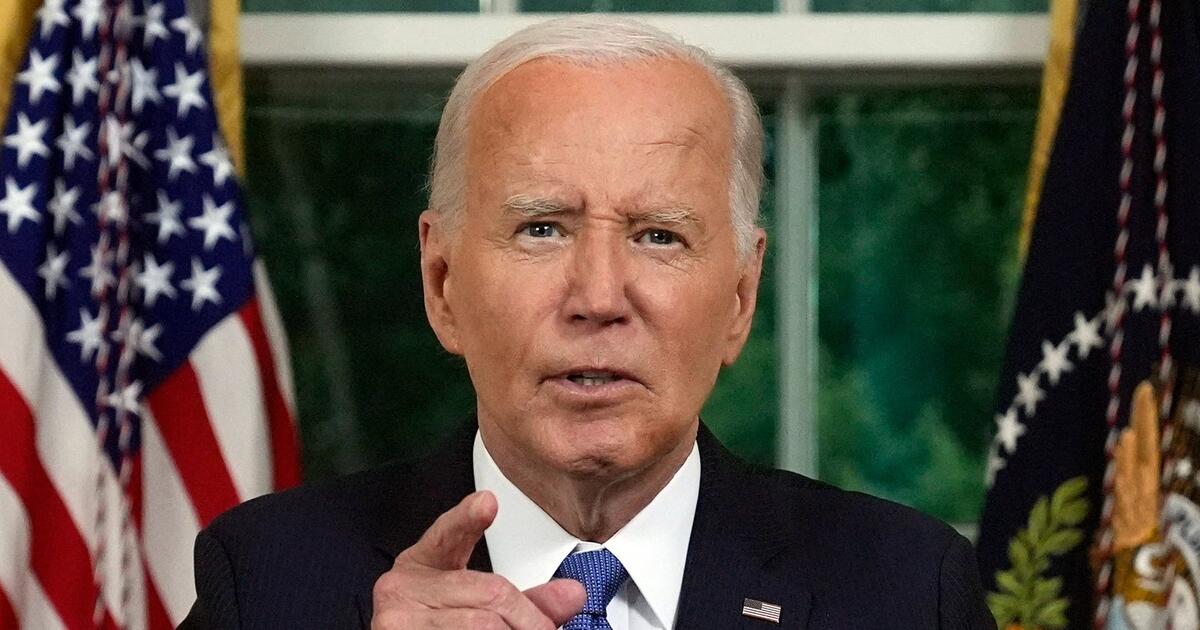

Address to the Nation: Joe Biden Explains His Resignation and Future

Harry makes serious claims in TV documentary: Will Meghan never return to UK?

’90s TV Star: Mourning Brenda: American Actress Shannen Doherty Dies – Entertainment