Initially without a real plan, Casanova served the delusions of the Marquis d’Urfe by all means at his disposal, Cultural journalist Eckart Klismann writes in his biography of Venice. For nearly seven years, Casanova had been communicating with various pink primitives and secrets on behalf of the Marquis, “the supreme fool” and “the poor woman,” as he called her, even writing a letter to the moon and—to the marquis’ delight—receiving her ostensible reply, a rite of order, She brought in accomplices only to get him fired when they threatened to bust him.

In short: “As a free-spirited person who loved the life I had, I took advantage of the madness of a woman who wanted to be betrayed by someone else if not by me.” When Casanova fell into distrust in frustration in 1763, he took from her about a million francs in cash, gold, and jewels.

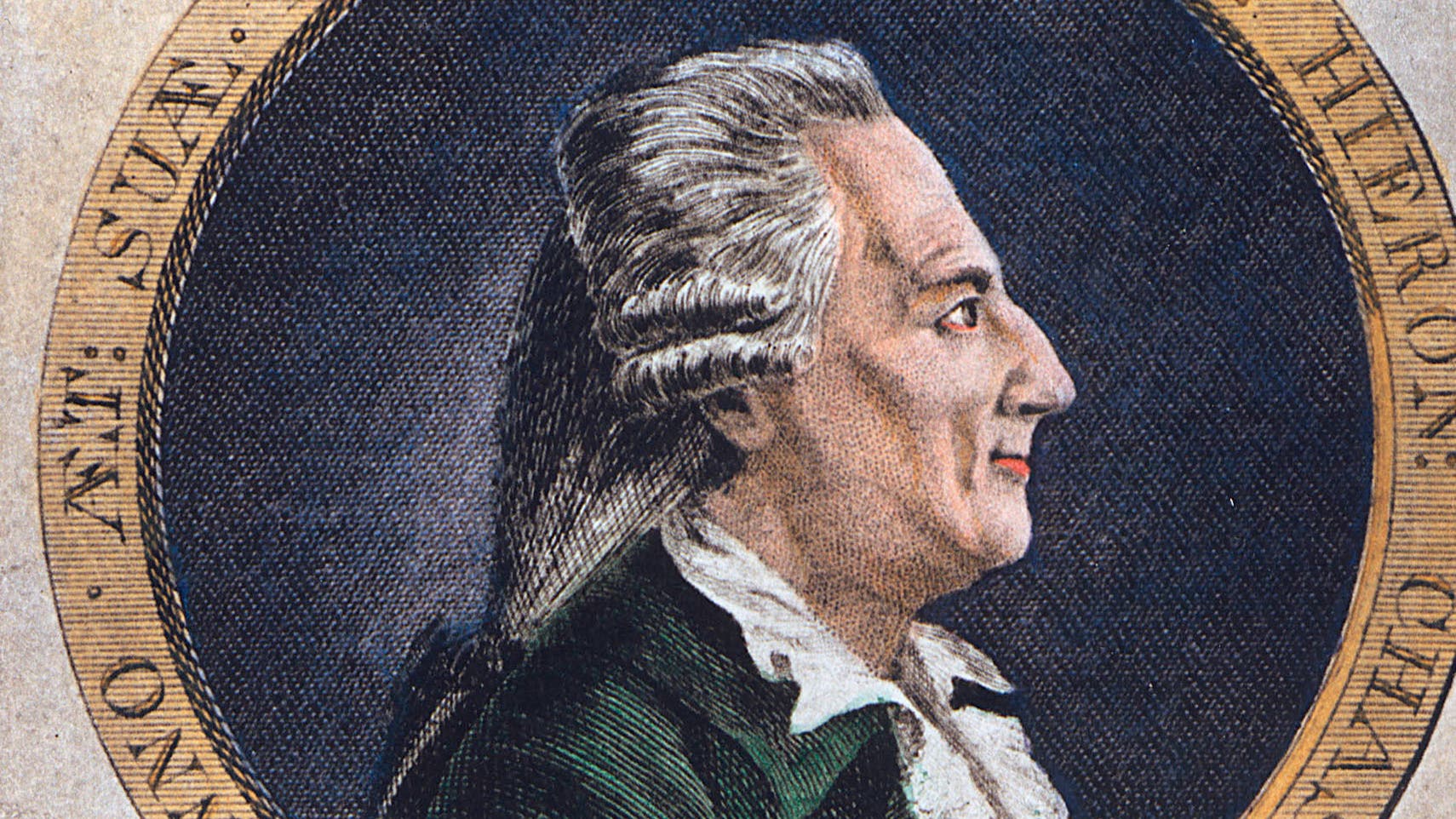

© TopFoto / picture alliance (Details)

Shepherd looking for a librarian | Casanova initially rejected Joseph Carl Emanuel von Waldstein’s offer. Ultimately, however, the need for security seemed to outweigh the dislike of the provinces.

Casanova also faithfully records the not-so-pleasant events that followed in his bohemian office: the Marquis, having broken up with him, left Casanova in the early summer of 1763, hastening somewhat towards London. But there he ran out of luck. An actress and adventurer named Marianne de Charpillon dismembered him, gave him hope, made him flounder without giving him the slightest favor—and emptied his bulging pockets. After a few months, the duped crook was as good as penniless and fled back to the mainland due to heavy debts.

Turbulent travels across the continent followed, meeting him with old (nephew d’Urfe) and new adversities (the morally strict Empress Maria Theresa). It seems as if the man who boasts in the memoir that he “never wanted to worry about his future as a philosopher” has developed concerns about the future over time. However, neither Frederick II (1712-1786), with whom he wandered in the garden of Sanssouci, nor Catherine the Great (1729-1786), who received him three times in St. Petersburg, gave him the diplomatic career he had hoped for.

In the end the winds deserted him to Deux – and Casanova hoped to get away from there to the end. On September 7, 1795, Charles Joseph Clary-Aldringen (1777-1831), grandson of the Prince de Ligne and a friend of Casanova’s youth, wrote in his diary that Venice had seriously decided to leave the Deux – because of all the troubles he had had there for the past ten years, but above all Because of the “daily insults” that the Count inflicted on him, he was evidently weary of his guest. “From time to time he charges him with the costs of his accommodation,” Clary wrote, “and they are really not that great, only 400 guilders a year.” “I would be very sad if we really lost him (…) Waldstein would also be very sorry, not for Casanova but for himself, because it is vanity to have such a famous and extraordinary man as Casanova with him.”

It didn’t come to that. Giacomo Casanova, who had left so much in his life when things got uncomfortable, for want of an alternative, stayed at Deux, where he died on 4 June 1798 at the age of 73.

“Alcohol buff. Troublemaker. Introvert. Student. Social media lover. Web ninja. Bacon fan. Reader.”

More Stories

“Time seems to cure long Covid.”

Science: The use of artificial intelligence is changing the way hospitals operate

Simple recipe: sweet cream cheese slices from the tray